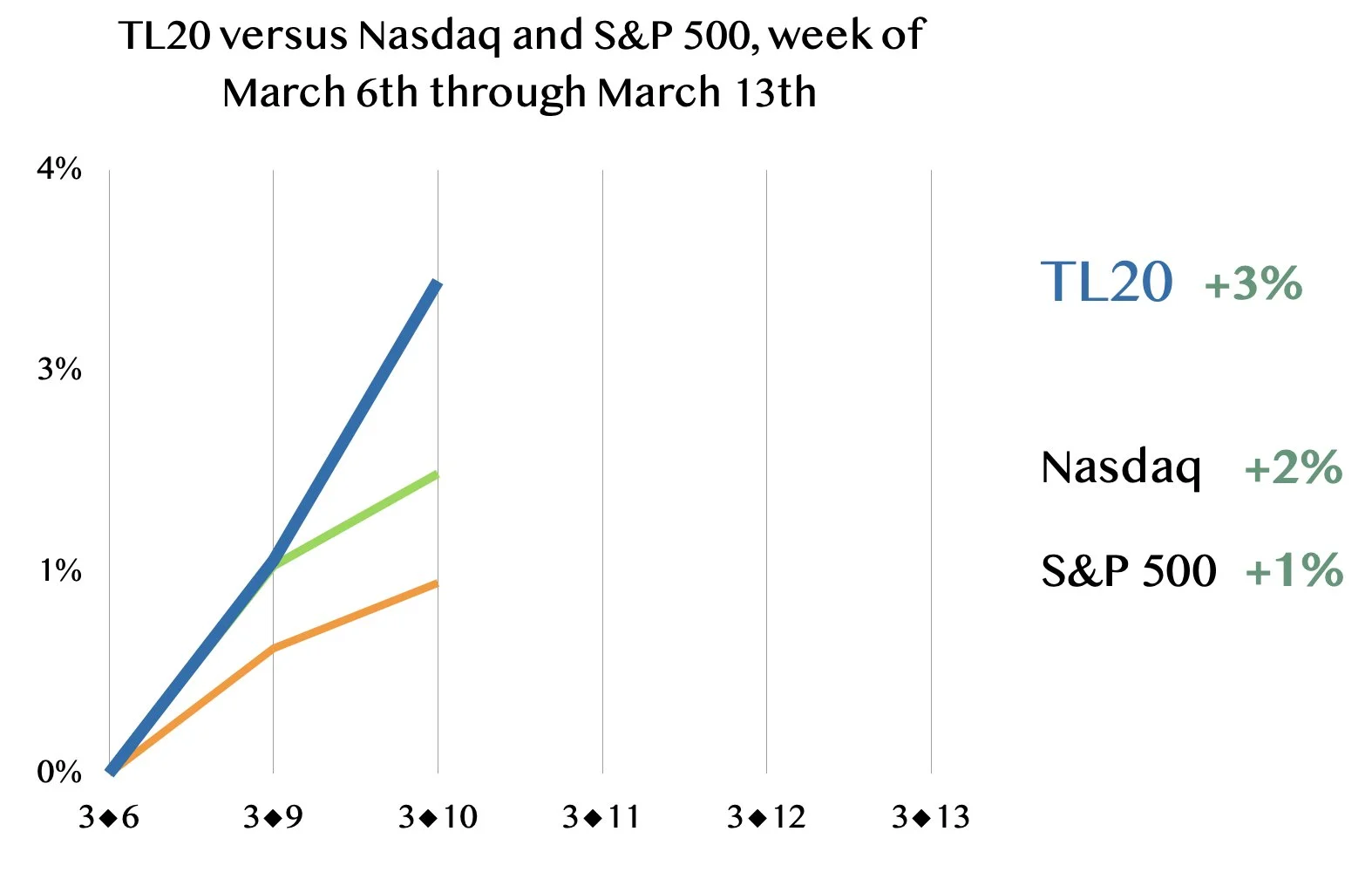

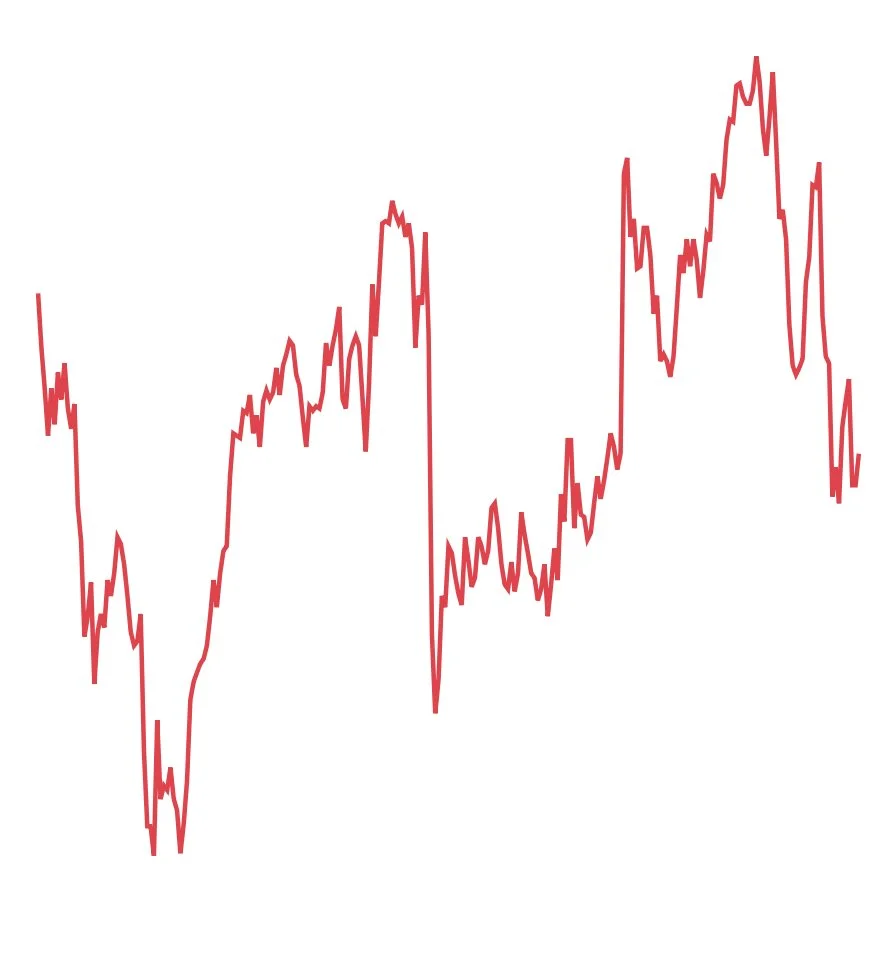

TL20 leads benchmarks

Year-to-date, the TL20 group of stocks to consider is up eight percent, better than the two-percent decline of the Nasdaq and fractional decline of the S&P 500. Read about the TL20

Full disclosure

Limited-time offer for new subscribers: $1 a week for four weeks

It’s funny what is trending Tuesday morning: big cuts in price targets for software stocks even as tech companies are doubling-down on the artificial intelligence-generated code that is causing havoc.

ServiceNow, Salesforce, Hubspot and Zscaler are among names seeing price targets slashed at various brokers Tuesday morning. These price target cuts are mostly still accompanied by Buy ratings or the equivalent.

The argument is not that the companies are in trouble. Rather, the analysts are trying to find what the bottom is in stock valuations, so they are proactively cutting the valuation multiples they put on these stocks.

I was certainly caught by surprise to learn this morning that Google’s YouTube has surpassed Walt Disney to become the world’s biggest media company, according to an estimate by Michael Nathanson of the eponymous Moffett-Nathanson research house.

Nathanson’s lengthy report is full of several original observations. He writes that the comment by Google on its most recent earnings call that YouTube made “over $60 billion” in revenue in 2025 implies actual revenue of $62 billion. That is larger than Disney’s reported $60.9 billion when one strips out the amusement parks revenue for Disney, he notes.

I’ve made some dumb mistakes in my time, but picking Oracle stock for the TL20 group of stocks to consider in August has to be one of my dumbest. The shares are down 33% since then at a recent $150.72.

I should have gone with my gut feeling in January of last year, when the news of Oracle partnering with OpenAI and SoftBank for a massive data center project, “Stargate,” came to light. It seemed exorbitant at the time. What we now know is that it has become a huge point of customer concentration for Oracle since then given how much of its outlook is tied to OpenAI as a customer.

Micron Technology shares are up 33% this year so far at a recent $378.75, and have more than quadrupled in twelve months, all driven by the incredibly tight conditions of DRAM supply. The latest stats from the Semiconductor Industry Association show DRAM prices up thirty percent, month to month, in January.

Will the stock crash when DRAM prices stop rising? Well, probably cool, but not crash, in my view.

We saw in December how rising DRAM prices are driving Micron’s profit margin way, way up; we’re going to hear again from Micron a week from Wednesday. Citigroup’s Atif Malik, who’s bullish on Micron stock, asks a fundamental question this morning: Is it different this time?

Shares of chip equipment maker BE Semiconductor are down sixteen percent today on a news headline about slight changes to the design of “high-bandwidth memory,” or, HBM, the fastest kinds of DRAM memory for artificial intelligence applications.

The development is certainly not fatal to BE, but it shows you just how much the stock is tied to a very specific sense of a payoff from one aspect of the AI trade.

In brief, the development, as identified by Pierre Ferragu of New Street Research, who has been following BE Semi’s business assiduously for quite some time, is that the DRAM community decided to change requirements for the “thickness” of the HBM parts. HBM is made of a stack of DRAM chips. They’re specified by committee to have certain dimensions. The latest thinking of the committee is written up this morning in a longish article by ZDNet Korea’s Jang Gyeong-yun.

Software maker Samsara, which sells purpose built hardware and software packages to run fleets of vehicles — logistics companies, school bus operators, etc. — is one of the many promising software stocks that has struggled for a while now. The shares were off sixteen percent heading into Thursday evening’s earnings report.

It turned out to be a very favorable report, and now the stock is up about eleven percent, pre-market, at $32.50.

Will it stick? That’s the question. This is the third quarter in a row where the shares are seeing double-digit gains, and yet, Samsara has tended to give up those gains in past in relatively short order.

Most of the time when Marvell Technology reports earnings, its shares sell off. In five years, the shares sold off a dozen quarters, according to FactSet data. So, the stock being up almost twelve percent Friday morning, in pre-market trading, at $84.70, is cause for celebration.

Marvell’s results and outlook came in just fine, though I’m inclined to see competitor Broadcom as the better bet.

Like Broadcom, Marvell helps companies make custom AI chips that they increasingly use as alternatives to chips from Nvidia. While Broadcom has six customers, Marvell has two, Amazon and Microsoft.

Enthusiasm for Marvell rests in it suddenly being the budget way to play the AI trade, if you will. Marvell shares are cheaper: they trade for under eleven times next year’s projected earnings per share, while Broadcom trades for under sixteen times. They’re both cheaper than a market, but Marvell even more so.

When chip giant Broadcom reported in December, the key issue was the company having to absorb greater costs in order to support new business with AI startup Anthropic. The result was going to be “deterioration” of the company’s gross profit margin, CEO Hock Tan said back then.

But, last night on the company’s first-quarter conference call, Tan walked back that assertion. He said they now expected to hold their company’s gross profit margin steady at the 77% it was for the quarter just ended.

“On further study, relative to even comments that I did make last quarter,” said CFO Kirsten Spears, the impact of rising costs is “not going to be substantial at all. So I wouldn't worry about it.”

After a continued heavy earnings schedule, we now have over three hundred earnings reports of merit on which to reflect.

The trend is clearly still in favor of “infrastructure” stocks, things such as semiconductors and chip-equipment makers and computer system vendors. Investors are still dumping software names.

Recent earnings winners in infrastructure include Applied Optoelectronics, following a report last week that sent its shares soaring by 57% the next day — after having already gained 54% leading up to the report.

Even the most bullish analysts cautioned investors not to take too seriously Applied Opto’s extremely bullish scenario for data-center-related sales of $4.5 billion by the middle of next year.

“Try to imagine Claude Code writing a distributed system for inline inspection of traffic and detecting any cyber issues!”

The past forty-eight hours of earnings are pretty dismal. Many of the companies seeing upward stock moves are companies whose shares have been weak for a long time and are seeing a minor reprieve, including software makers Box, GitLab and Asana. In the case of GitLab and Asana, missing revenue for the quarter doesn’t bode well going forward.

Database maker MongoDB, which had been one of the biggest turnaround stories in software last summer, plummeted 23% because of a disappointing forecast. The sticking point at the moment is that the company’s additions to its database of artificial intelligence stuff is not generating a lot of revenue — a familiar story across the software landscape.

The big surprise was Tuesday’s 23% jump in shares of hydrogen fuel cell maker and distributor Plug Power. They have heavy, heavy assets, such hydrogen production plants in Tennessee, Georgia, and Louisiana.

“The big impediments to enterprise adoption are things that can be solved with data engineering.”

I noted back in December that the double-digit rise in the price of DRAM memory chips globally is great news for Micron Technology — indeed, it has powered the stock up 44% this year at a recent $411.54 — but it is a big headache for companies that have to build things with the increased expense of DRAM.

The debate at the moment is whether Apple will be hurt by the memory tax, which has the possibility of either driving up its iPhone prices or forcing Apple to eat the cost and sacrifice profit margin. Apple shares are down two percent this year, at $266.18, in line with the Nasdaq Composite.

The negative view is expressed in straightforward terms by, for example, UBS analyst David Vogt, who rates Apple’s stock Neutral, with a $280 target, writing Monday that the rise in memory prices will reduce prospects for whatever arrives this fall as an “iPhone 18.”

“The outlook is increasingly cloudy” for iPhone, writes Vogt.

Shares of CoreWeave, the debt-laden provider of artificial intelligence data centers, are down 16% Friday morning at $81.65.

This is the fourth time the company has reported quarterly results since coming public on March 28th of last year. And it’s the fourth time the stock is selling off on the numbers.

Funny thing, though, CoreWeave has actually been a terrific performer since the IPO, up 144% through Thursday’s close, and 36% this year.

Clearly, the rhythm of this stock is that it sells off on earnings and then buyers swoop in.

So what is there to like and not like this time around? Basically, the company has huge demand but profit keeps slipping farther into the future.

Wednesday evening is one of the most consequential evenings of the earnings season, with Nvidia reporting its January-ending results, which easily topped expectations.

I’m surprised by the weak response to Nvidia Wednesday night — shares up just a fraction at $195.94. So is Simon Leopold of Raymond James, who writes, “we are a little perplexed by the muted stock response.” He reiterates his Strong Buy rating and hikes his price target to $291 from $272.

Certainly, the results are something to cheer about. Back in September, when I rebalanced the TL20 group of stocks to consider, I had hypothesized that Nvidia would show less upside every quarter. But, I was wrong. The company’s sales forecast tonight is the strongest in almost two years.

We are still very much in the thick of earnings season. This week brings reports from a lot of companies whose stocks have been real dogs this year. The average decline since the start of the year for the twenty-eight companies having reported through Monday morning is eleven percent. So, there are a lot of names that you see jumping on reports that were not as bad as feared for companies whose stocks were due for some kind of rebound.

One name that’s seeing a noteworthy pop is Circle Internet Group, the creator of the “USDC” stablecoin, which went public last June. The stock is up twenty-nine percent at $79.43, which appears to be a reflection of a belief in the company as a kind of “safe haven” in crypto-currencies, if that has any meaning.

Almost all of Circle’s revenue comes from interest earned on the fiat money people give Circle to use their USDC crypto dollars. It’s called “reserve income.” (The fiat dollars are mostly held in a money-market fund run by BlackRock, the rest in global bank accounts.)

The technology of artificial intelligence data centers is such a hot, hot theme these days that it has the potential to be a battleground for investors.

The most vivid example is a company called Accelsius, which has developed the next generation of technology to cool the power-hungry GPU chips from Nvidia that are filling up those data centers. The technology could be worth billions of dollars in annual sales someday to Accelsius.

Accelsius is forty-three-percent owned by a conglomerate named Innventure that came public in 2024. Last week, two major shareholders representing over ten percent of Innventure were in open revolt, decrying what they claim is Innventure’s “reckless” mismanagement of the Accelsius opportunity.

What’s at stake is both a potential winner in AI and also a very interesting attempt to create a new kind of quasi-venture capital business of tech funding, what Innventure management argues could someday be the next Berkshire-Hathaway.

“Innventure is different from anything you’ve ever seen, and that has been both a blessing and a curse,” Innventure’s CEO, Bill Haskell, told me last month in an introductory meeting via Zoom.

I had no idea at the time that what was brewing was actually a big drama.

Stock analysts who cover cyber-security firms such as Palo Alto Networks and Check Point spent the weekend digesting the latest development in artificial intelligence that promises to destroy commercial software.

The AI startup Anthropic, which makes the “Claude” series of large language models, on Friday announced a new product offering, “Claude Code Security,” which will automatically find bugs in computer code and propose fixes.

The Anthropic announcement follows the announcement of similar tools in recent months from OpenAI and Google, so that all three of the top AI model makers now have some kind of security-tool offering.

The stocks have taken a little bit of a hit since Friday’s announcement. Palo Alto shares are down two percent on Monday at $145.34; Check Point is down two percent at $155.43; Zscaler shares are down ten percent at $143.76, following a five-percent drop on Friday; Cloudflare is down almost nine percent at $161.34; JFrog is off six percent today at $35.55, but plunged on Friday, losing almost a quarter of its value.

On Thursday, following an upbeat earnings report in the morning by software maker NICE Ltd., I spoke in the afternoon with CEO Scott Russell. The shares were enjoying a NICE bounce of about thirteen percent as we spoke, rising to $111.55.

My main question for Russell was about the ongoing terrible nature of the software cohort of stocks. Unlike 2021, when it seemed every single software stock got the thumbs up, investors today are deeply sour on the whole group.

Russell’s view is that eventually investors will pick individual companies and stocks as winners and losers in the AI race.

“In 2021, there wasn’t the open question around what is that forward revenue going to look like,” says Russell, meaning, what will revenue look like for any software company years down the road.

He’s right: there wasn’t a massive existential threat back in 2021, before ChatGPT arrived.

Thursday’s earnings reports continued a trend of strength in infrastructure linked to artificial intelligence, including BE Semiconductor and chip-equipment vendor Onto Innovation. Despite strong reports, both stocks sold off given that their shares had been way, way up heading into the reports.

By contrast, software and services companies are either trading down, such as Weave Communications and LegalZoom, or are seeing a mild jump in stock price after lagging since the start of the year, such as Five9, OpenDoor, Workiva, Appian and Bandwidth.

BE Semi’s ordinary shares traded on the Amsterdam exchange sold off by eight percent on Thursday despite a very positive report in the morning. It was the first time the company’s sales topped expectations after four quarterly misses. The shares subsequently rose four percent in Friday’s Amsterdam trading, and the American Depository Receipts were up five percent on Friday in New York trading, at $214.88.

I wish I had something shocking to report, but the first batch of this week’s earnings reports are sadly predictable: chip and chip-related names are doing great while software is doing not so great.

Shares of chip giant Analog Devices are higher Wednesday, and shares of chip-equipment maker Camtek were trending higher at the open, though they have since declined. Both stocks have had big gains already since the start of the year.

In contrast, shares of software makers Palo Alto Networks and Similarweb are going sharply lower.

For Analog Devices, which reported this morning before market open, the one-point gain today, to $342.42, is more muted than the past two quarters’ jump in price. But the basic message is that sales and profit trends continue to reinforce a multi-quarter recovery in the company’s very broad and diverse chip market.

That is confirmation of what we heard last month from peer Microchip about favorable trends for analog chips, and subsequently from that other analog chip giant, Texas Instruments.

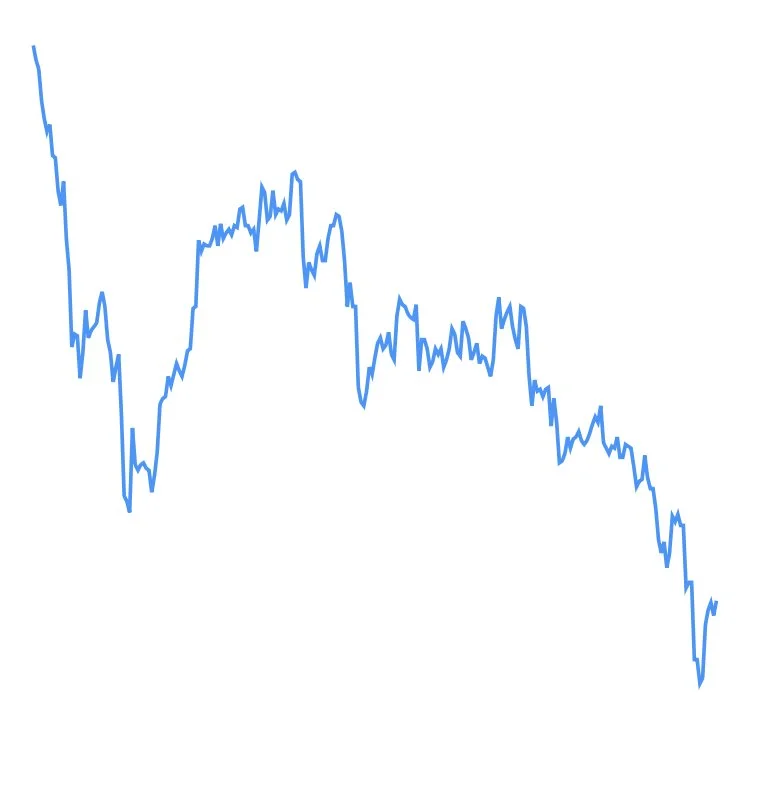

It’s no secret that we are in a terrible moment for crypto-currencies. The price of Bitcoin is down twenty-three percent this year, and down thirty-one percent in twelve months. Coinbase, the standard bearer for “investing” in crypto’s growth, is down thirty-nine percent in the past year.

The two most prominent recent initial public offerings of crypto firms, Bullish, the seven-billion-dollar Bitcoin trading exchange, and Circle Internet Group, the creator of the “USDC” stablecoin, are down fifty-five percent and twenty-nine percent since their respective IPOs.

And Monday, the latest hopeful, BitGo Holdings, received its first coverage from Street analysts after a more-than-forty-five-percent decline from its IPO on January 22nd to a recent $10.22.

“Those are the kinds of things people have been trying to figure out with large language models in general, is how to give them a brain, basically.”

“The problems of the grid that we solve are going to be persistent for a very long time. And we're in a unique position to take advantage of that.”

“If a JP Morgan or a United Airlines is down for hours because their observability solution isn’t working, was that really worth the cost of deploying a vibe-coded startup’s observability system?”

There’s a ritual now in the AI Trade, which is, guessing which well-heeled customers are the next giant customers for a given vendor.

Shares of networking vendor Arista Networks are up almost eight percent Friday morning at $145.20 on speculation that the company will add another two big customers this year. Sales at the moment are dominated by Microsoft and Meta, which have each for a long time been more than ten percent of Arista’s annual sales.

CEO Jayshree Ullal Thursday evening indicated that there’s potential this year to add two more customers of the same significance.

Amit Daryanani of Evercore ISI thinks the two potential unnamed customers might be Anthropic and Oracle. Rosenblatt Securities’s Mike Genovese thinks it will be Oracle and Alphabet’s Google. Raymond James’s Simon Leopold thinks it will be either Elon Musk’s xAI (now part of his SpaceX) or Oracle.

Wednesday morning’s earnings reports are pretty lousy for software names, especially Shopify, the e-commerce software and services giant, whose shares are down thirteen percent in spite of the fact that the company announced a new two-billion-dollar buyback authorization.

When a stock sells off despite a big buyback, that’s bad.

Indeed, one bull, Arjun Bhatia of William Blair, who has an Outperform rating on the shares, is bemused. “The reaction is surprising, and does not reflect the strong growth fundamentals this quarter,” he writes.

“Perhaps the only item that stuck out in the report was Shopify’s first-quarter FCF margin guidance of low to midteens,” he writes, though he thinks that should not be enough to sink the stock.

Although it sometimes seems like Micron Technology has to go up every single day — up forty-seven percent in three months — it doesn’t, actually. Tuesday, it was down over two points at $373.25. That is in spite of more good news for Micron Tuesday about the raging price of memory chips.

The current short supply of DRAM, what has been dubbed a “supply shock” that is driving prices sky high, is still not fully appreciated, writes Deutsche Bank’s Melissa Weathers on Tuesday. She reiterates a Buy rating and raises her price target on Micron to $500 — another thirty-four percent higher from here — based on her expectation DRAM supply tightness will last through 2028.

“We see DRAM tightness continuing through 2027 into 2028, though we see some relief in 2027 as new supply comes online,” she writes.

It’s all good news Tuesday morning for earnings winners Datadog, chip-equipment maker Entegris, Spotify, and Austrian specialty chip maker ams-Osram.

Entegris a continuation of the good news we’ve seen of late in everything chip-equipment-related, and ams-Osram continues the semiconductor bull run. Spotify is a bit of a specialty case, having topped expectations for users (“MAUs”) amidst what has been a very spotty, ahem, track record for user stats.

Datadog is especially interesting because of the ongoing slump in software stocks. The stock’s jump today follows seven percent gain for competitor Dynatrace yesterday (discussed in this week’s podcast.)

The stock is up sixteen percent Tuesday, at $132.45, though still down three percent for the year and down ten percent in the past twelve months.

The giddiness about Datadog amidst a very weak software market is evident in the headlines from the Street this morning. “Irrational pessimism collides with reality,” writes Brian White of Monness Crespi Hardt, who reiterates his Buy rating and $225 price target.

Oracle reported results after market close on Tuesday, and the stock jumped 9% in after-hours trading, and is up over 12% Wednesday morning, at $167.47.

The favorable response is mainly in response to the company’s impressive cloud computing sales growth of 44%.

However, nothing about the report changes my feeling this has become a bad proposition.

The company has gone massively into debt, they’re diluting shareholders, they’re eroding their margins, and, worst of all, we don’t know just how much the company is exposed to one giant customer, OpenAI.