Tarana Wireless: One of those great unsolved tech problems that could go big

Startup Tarana Wireless has been working for fifteen years on what it calls “fixed-wireless reinvented,” the ability to send as much as a gigabit of Internet to your home without a line of sight from the tower. It could usher in an age when wireless is indistinguishable from cable and fiber in closing the digital divide.

The market for home wireless broadband is ruled by giants such as T-Mobile and Verizon Wireless who own vast swaths of valuable real estate known as the electromagnetic spectrum. Despite all the resources of those wealthy outfits, many of us get little or nothing in the way of broadband service even if we’re willing to pay handsomely for it.

Wireless broadband service, although it has lured millions of customers away from cable and fiber, is ultimately too expensive to be economical for even the largest carriers. Longtime wireless market observer Craig Moffett, of the eponymous MoffettNathanson Research firm, notes in a recent report that “the financial upside from fixed wireless access,” the technology of beaming a broadband signal to a radio on the side of a house or apartment building, “is likely to be quite limited.”

Because of how little revenue fixed wireless brings in relative to the enormous capital expense to provide the service, “we continue to believe that its market impact, as well as its ability to generate incremental growth for the TelCos, will be limited,” wrote Moffett.

A Tarana Wireless subscriber radio that could be on the side of a house or multi-tenant dwelling.

The problem is very basic. Carriers have spent hundreds of billions of dollars to license the electromagnetic spectrum. Once in possession, they must build out radios to blanket a service area.

To deliver tens or hundreds of megabits, they must deploy a lot of radios, for most can’t transmit very far if they have to provide a very high-bandwidth signal. After all that investment is made, the carriers have to compete with the gold standard in broadband, the incumbent cable provider, capping what Verizon and T-Mobile can charge per home, per month.

It stands to reason there should be a great business for anyone who can build a technology that can spread the wireless signal to homes at a far lower cost.

“The reason this company is exciting is because we’ve got a depth of technology addressing a very tough problem,” says Basil Alwan, chief executive of fifteen-year-old startup Tarana Wireless.

I was talking with Alwan in an upstairs conference room last week in one of those identical, prairie-style office park buildings you find in Milpitas, a strip mall town just below Fremont, California, at the base of the San Francisco Bay.

Fifteen years ago, Tarana’s co-founder, Sergiu Nedeveschi, who serves as the company’s chief science officer, started building with his fellow engineers a fairly remarkable wireless technology, and began patenting it.

Alwan sees an addressable market, globally, for broadband wireless of a hundred million homes, most of them in either unserved or underserved markets, that may be worth over fifty billion dollars, annually. “There’s a long-term play here for a big business,” he says. “The opportunity is massive.”

Their technology can transmit for distances of many miles, serving hundreds of homes off a single radio costing a mere $15,000. It can transmit in spite of leaves and fog and physical objects, where most broadband radio transmitters must have “line of sight,” a clear path through the air from the tower to the home.

Most impressive of all, perhaps, the radios can operate not only in the expensive electromagnetic frequencies where the carriers have exclusive sway, but in unlicensed spectrum just like WiFi, where anyone can put up a radio.

“It’s the only technology, really, that's come along in the last decade that fundamentally can have an impact on the cost of high-performance broadband,” says Alwan.

The profound implication, says Alwan, is that “wireless technology has advanced to the state where, five years from now, we're going to look back and people aren't going to blink when they say whether it's wireless or fiber — it’s not going to matter.”

On its face, Tarana’s story has little relevance for a TL reader. The company’s technology is unique, making it an outlier. And the company, which has gotten over four hundred million dollars in venture capital and angel money, is still private. You may not be interested if you can’t trade it, I realize.

Look a little deeper, however, and there are things we can learn here.

The Tarana technology speaks to the enormous increase in processing power that is making wireless, especially unlicensed wireless, economical in a way that futurist George Gilder foresaw decades ago. In his 2000 book Telecosm: a world after abundance, Gilder predicted that creative use of unlicensed spectrum, using smart radio technology, would someday make wireless service like “the endless waves of the ocean itself,” boundless in the digital services it can deliver to every individual. Tarana is a peak at that possible future.

A second thing to consider is that Tarana, which has substantial revenue for a startup, and which may reach positive free cash flow at the end of next year, could at some point in the not-too-distant future be one of the most interesting tech initial public offerings in a long time. It behoves one to become familiar with how the company may be re-shaping the regime of wireless.

“This is one of those moments in technology similar to the cell phone,” says Alwan. He sees an addressable market, globally, for broadband wireless of a hundred million homes, most of them in either unserved or underserved markets, that may be worth over fifty billion dollars, annually. “There’s a long-term play here for a big business,” he says. “The opportunity is massive.”

STRANDED

Anyone who has ever lived in someplace rural, or even rustically suburban, has had this modern frustration: trying to be connected to the grid where the phone company simply doesn’t care, and the cable company cares but wouldn’t dare to spend the money to dig a trench.

Twenty miles south of Milpitas, like a funnel between the Santa Cruz mountains ushering Silicon Valley to the Pacific Ocean, sits the tony town of Los Gatos. You wouldn’t think there would be a problem getting broadband service in Los Gatos, which is hardly rustic. There are enough wine bars on the main drag and enough millionaires from nearby Netflix and Roku to justify any amount of connectivity spending.

In Los Gatos, however, “Nobody gives a shit,” meaning, the local operator, Comcast, “because the density’s not there,” says Alwan, who happens to reside in the Los Gatos hills, five minutes from downtown.

“It’s a density equation, it’s not whether you are wealthy or not wealthy,” observes Alwan. “If you can’t get enough homes” on a fiber run, "you can’t make the math work” for a service provider business.

Comcast was not about to be his savior when he asked for fiber-optic service to boost his home broadband. “They said they would do it if I spent seventy thousand dollars to help them defray the cost of the cable coming up the street.”

Alwan, who is a serial entrepreneur from the computer networking world, is happy to dabble in technical stunts on his own. He tried solving his home broadband dilemma by procuring radio systems from the likes of Cambium Networks and Ubiquiti, the best-known publicly-traded radio equipment makers.

“I got maybe twenty to thirty megabits per second on a really rare day,” he recalls of that experiment.

It was around that time, about four years ago, that a friend in the satellite industry told Alwan, “you gotta meet these guys, they do something really curious,” meaning Nedeveschi and team at Tarana.

What they were promising was “hundreds of megabits per second, up to a gigabit, non-line-of-sight, with heavy interference, in unlicensed spectrum, which is the Holy Grail,” of wireless, recalls Alwan.

Fixed wireless technology has a long history of unmet promises. “It’s like nuclear fusion,” says Alwan, “it’s very hard to obtain; it’s a very checkered area, so there’s good reason people are skeptical.”

Alwan told the engineers, “I actually don’t believe you, come up to my house.” In Los Gatos, the Tarana team set up their radio, a white box roughly the size of a laptop computer, on a tripod, and pointed it at a building nine miles north in San Jose. “I was suddenly getting a hundred and seventy megabits [download speed] — Wow! In a prototype!” recalls Alwan. “This is nuts,” he thought at the time, “this is really cool.”

Having had something of an epiphany, Alwan joined the board of directors of Tarana. Nedeveschi and team were the classic startup, a bunch of engineers inventing without any business infrastructure. “They just hadn’t built the front end,” is how Alwan characterizes the skunk works.

“They had one sales guy, and I said, This is not a sales guy,” Alwan recalls. “He couldn’t call.”

At the time, Alwan was running the “core routing” network equipment division of equipment giant Nokia, having sold his previous startup, TiMetra, to Alcatel-Lucent, which had merged with Nokia. He tried to get his boss, then-CEO Rajeev Suri, to buy Tarana.

His pitch was unsuccessful. Nokia was going through turmoil at the time, in 2021, as the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns were hitting the equipment market. Nokia’s sales growth was down to low single digits, and the company had embarked on an ambitious cost-cutting initiative.

“I finally said, you know, look, I'll jump in, and I'll run this for a while,” he says. "I've been running it ever since, about three years, and I'm having a blast.” Under Alwan, the company began shipping product a year and a half ago.

After fifteen years of racing to the beginning of the road, for Tarana, things are a bit like a famous line from comedian Eddie Cantor, says Alwan. “He got famous after twenty years, and everyone called him an overnight success,” observes Alwan. “Cantor said, I guess it takes at least twenty years to make an overnight success — well, yes, it does.”

THE BLACK ART

Engineering things to work in radio is an art, a black art, they say. Modern wireless has been helped partly by the increases in processing power of computer chips. But fast chips can only go so far.

The Tarana engineers "didn’t take a Broadcom chip or a Qualcomm chip, and just write some new software, which is the typical startup approach, don’t do too much, just enough,” says Alwan.

Instead, to get high-bandwidth transmission without line of sight, Nedeveschi and team had to find a way to operate in and around the dominant wireless transmissions in the “mid-band” spectrum, WiFi and cellular. (Mid-band is one of the most crowded portions of the electromagnetic spectrum, frequencies of two to seven gigahertz.)

“Neither of those were built for home broadband,” says Alwan of WiFi and Cellular. “If you were going to build something in that mid-band spectrum for home use, you would build it very differently.” Nedeveschi and colleagues “went with a clean sheet of paper.”

In dozens of patents over fifteen years, the engineers outline a grand symphony of wireless art. The base station radio that costs $15,000, and the laptop-sized subscriber unit, communicate using a plethora of techniques that manipulate not one but numerous antennae, sending each subscriber’s signal across multiple paths through the air. Signals can bounce off leaves or walls, and are combined into one intact message at the receiving end by coordinating what each antenna picks up.

The “multi-path” nature by which the signals are combined has “remarkable implications,” according to one of Tarana’s representative U.S. patents, number 11,831,372 B2, granted in November.

By coordinating multiple signals in multiple antennae, wireless interference, one of the biggest challenges of the crowded mid-band, can be reduced to a negligible level. The efficiency of the spectrum surges, and a single radio can serve an entire segment of a city network “with a single frequency channel, thus minimizing the need for a large amount of spectrum,” the patent relates.

Nedeveschi and team did more than come up with clever algorithms. They have designed and had “fabbed” (made by a third party) their own semiconductor chips to handle multiple parts of the radio system. That includes chips that “down-convert” from the mid-band frequency to an intermediate frequency that can be handled by a digital signal processor, a “baseband” chip, also a custom Tarana design, that filters, combines and cleans up the signals of many antennae. Even the chips that convert between the analog wireless signal and the digital realm are custom ADCs, analog-to-digital converters.

The Tarana circuit board with its custom baseband chip in the center. The Tarana engineers "didn’t take a Broadcom chip or a Qualcomm chip, and just write some new software, which is the typical startup approach,” says Alwan, “they started with a clean sheet of paper.”

All that custom work gives the company a head-start on anyone trying to approximate their invention.

“It’s going to be years before this can be achieved in merchant chips,” says Alwan in the conference room, referring to standard parts of the kind Broadcom and Qualcomm sell. Where Alwan is effusive, Nedeveschi speaks in a quiet, circumspect way, and has a habit of communicating a lot with a single glance. Asked if this can be done in standard chips, he simply shakes his head slowly with a slight smile.

Alwan with chief science officer and co-founder Sergiu Nedeveschi, holding their forty-five pound, $15,000 base station that can serve roughly a hundred fifty homes, for miles, with as much as a gigabit of service.

The natural processing power attained by chip-making improvements has allowed Tarana’s custom chips to become more efficient and achieve higher bandwidth with successive generations. Newer versions of the chips are pushing download speeds per subscriber from half a gig to a gig per second.

But the chips’ designs must still be unique arrangements of transistors in order to run Tarana’s algorithms efficiently. No amount of raw transistor speed alone will solve the problem.

EVEN WHILE POINTING AT THE GROUND

In the parking lot next to the headquarters building, Nedeveschi has set up a demo with a group of engineers. The subscriber laptop-sized radio is on a ten-foot pole, pointed at the transmitting base-station on the building’s roof. A large monitor shows the constantly changing measures of signal-to-noise and bandwidth for every “channel” of frequency in the mid-band. It is slightly overcast on this day. The receiving signal is getting remarkable bandwidth of perhaps half a gigabit per second.

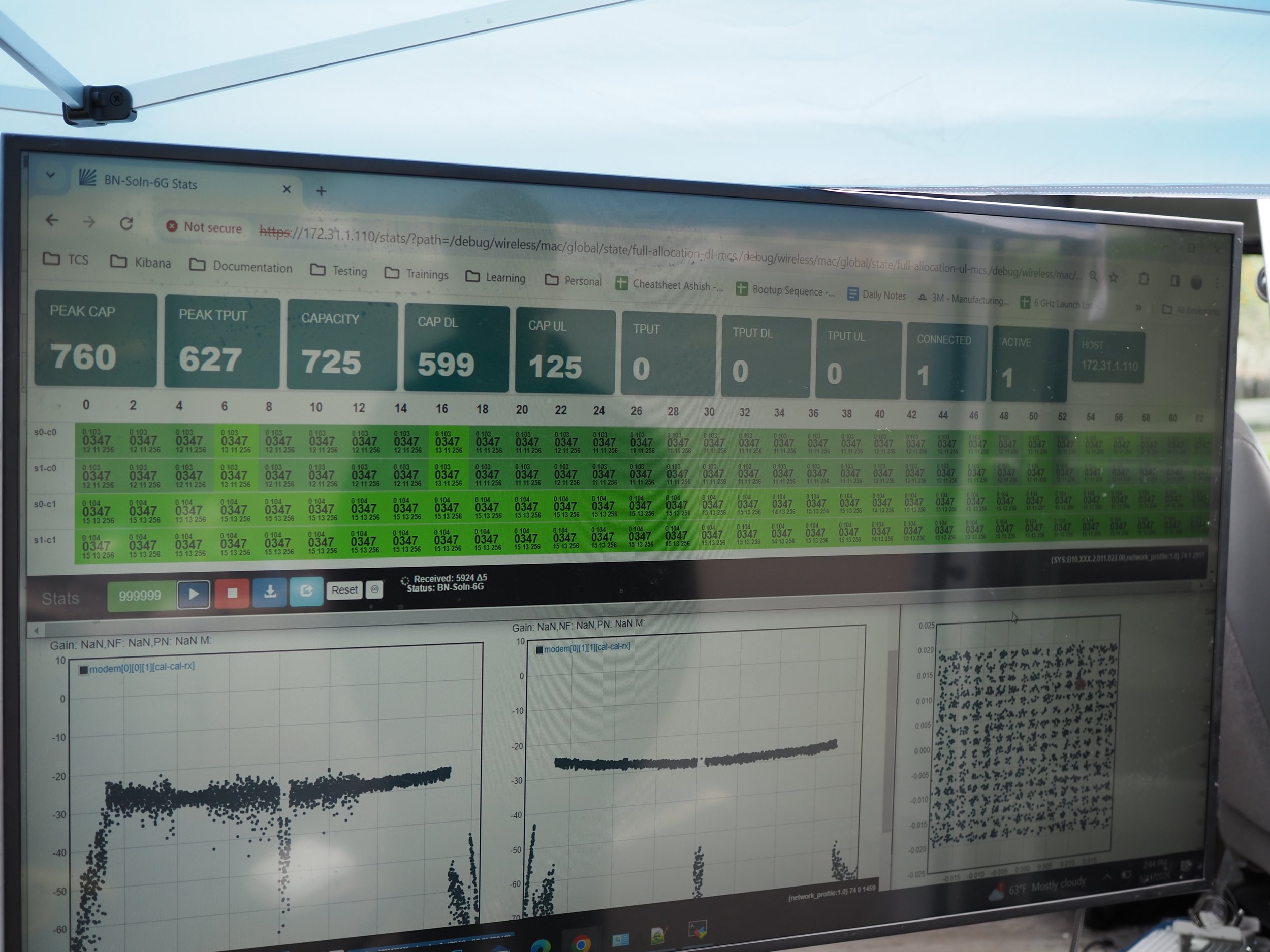

The big board in the parking lot shows status of throughput and interference, with peak throughput in this case of almost six hundred megabits per second download.

Nedeveschi has an engineer flip a switch and turn off the “special sauce,” the algorithm that eliminates interference. A nearby table full of laptops on WiFi simulate competing users whose activity invades the Tarana signal. As the switch is thrown, the interference rises precipitously, and the bandwidth plunges, simulating the usual state of interference. It’s a demonstration as ablation of the power of the Tarana technology to prevent interference.

Perhaps more striking, because the multi-path technology is working like mad to combine the many signals arising at multiple antennae, the radios can sometimes perform even better where there are obstructions in the path of transmission. Wireless signals can reflect off objects, which can actually compound the received signal, rather than reduce it.

Nedeveschi picks up the pole with the subscriber radio and swivels it away from the direction of the base station radio. The signal on the big board display gets better, the bandwidth level rises.

Even pointing at the ground, the receiving radio unit can continue to get a signal because of reflections that are figured out by the baseband processor.

He tilts the pole gradually until the receiving radio is pointing at a forty-five degree angle to the ground. The signal dips but is still strong. The black art of wireless has conjured bandwidth from obstruction.

“People have been testing our product, and they can't understand how it's doing this,” says Alwan. “They're literally befuddled.”

READY FOR LIFT-OFF

The overnight success is off to a decent start, Tarana having signed over two hundred service provider customers in twenty-one countries and forty-five U.S. states. Revenue in 2022 was $92 million. Alwan declines to disclose 2023 revenue, but says sales exiting the fourth quarter of the year were at a “run rate” of more than $150 million, and growth is “good.”

The business has been built so far on the “WISPs,” wireless Internet service providers, smaller telecom operators who may only serve a town or a regional market. In Bay Area towns such as Los Gatos, two providers using the equipment to serve residents and businesses are Sail Internet, and Tekify Fiber and Wireless, offering home and multi-unit dwelling plans with free installation of the radio, in some cases.

“Our bigger goal here is not rural,” says Alwan. “We’re better at rural, yes, we’ll do towns better than anybody, but you will also start to see us over-build cities.” Tarana has outfitted carriers for city centers, often in conjunction with an existing fiber-optic service.

The “sweet spot” for operators to deploy a $15,000 base station in a market is to get perhaps a hundred and fifty homes, initially, on a single radio, consuming plans offering download speeds of one hundred to two hundred to four hundred megabits per second. (Uplink speeds can be the same as download, depending on how the operator wants to price things, but, typically, in fixed wireless, as in cellular, uploads are slower than downloads.)

Tarana’s modeling of the math for a WISP is that it takes one tenth the money to serve a given area of thousands of “locations” as it does to build out fiber, where a location can be a house or a multi-unit dwelling or a hospital or another structure.

That comes out to the difference between, say, over two hundred million dollars in one example fiber build, once the fiber is dug and hooked up to the home, versus twenty-three million to put up a new tower, install Tarana radios, install the receiver at the home, and install any other cable or fiber the Tarana gear needs.

Those plans can bring in five hundred dollars in lifetime value from each customer a WISP signs. With a transmission range of potentially miles, the sweet spot for WISPs tends to be in “dense rural areas and even cities up to a certain density, says Alwan.

Carriers can stack Tarana radios on top of one another at the tower, to multiply several-fold the number of customers served in the same area, on the same frequency spectrum. Tarana has WISPs who compete using its equipment in the same physical area, their transmissions overlapping but not interfering.

“With our system, if you happen to be in overlapping spectrum, you're probably gonna be okay” as an operator, says Alwan. "You might have some impact, but it won't be nearly the impact you've seen historically” in the wireless business.

There is a prospect to grow beyond that WISP market. “There's a lot of larger guys that are putting us through the paces right now,” says Alwan, without disclosing names.

Things are afoot in regulation and in broadband funding that may make the market more interesting still.

Observes Nedeveschi, “In the industry, both here as well as internationally, a lot of regulators are migrating towards more and more options for shared spectrum rather than nationally-licensed spectrum that only one entity can use, which is really highly suboptimal.”

In other words, although the Tarana technology is unique, the paradigm of loosening the reins on the electromagnetic spectrum is taking shape as a global phenomenon. As Gilder foresaw, there is a growing awareness that technology can relax longstanding guardrails.

Carriers, suggests Nedeveschi, can amass mixtures of licensed and unlicensed spectrum, both the shared kind and some exclusives slices, that could rival the exclusively licensed assets of Verizon and other giants. “We’re making unlicensed workable,” says Alwan, “not just for low-speed rural links, which is what Cambium and Ubiquiti did, but, actually, a five-hundred-megabit link.”

There are pools of money for enterprising WISPs and others to go after. In the U.S., the Department of Commerce’s National Telecommunications and Information Administration, the NTIA, is apportioning $42.5 billion in coming years to what it calls “BEAD,” the “Broadband Equity Access and Deployment Program,” meant to close the so-called digital divide. That money can go to any number of things, including cable, fiber and satellite. Each state has to put together a plan for how they would use the money.

“We're very involved in helping states understand that if you don't have enough money for fiber, here's a nice alternative,” says Alwan. “And it will be the most cost-effective, high-performance solution out there.”

Tarana, like any small company, has the primary challenge of how to become a big company. The company was valued following its most recent round of funding at almost a billion and a half dollars. “It wouldn’t take much” to reach a billion dollars in annual revenue, muses Alwan, perhaps three to four million homes using service based on the equipment.

“In the U.S., there’s fifteen million or so homes that are unserved or under-served,” he explains. “And there’s fifty-five million that have exactly one choice, cable.”

One challenge is getting the word out for Tarana’s technology. A souvenir tee shirt represents the jumble of competing signals, right, that interfere with one another, versus the order that Tarana’s algorithms can convert that into.

“You know, three to four million homes, globally, is definitely something that’s within the realm of possibility,” he says. The company is currently pursuing a “top-up” of funding, but there is no “step-function” plan to increase investment, says Alwan, although “I’m not saying we wouldn’t” if the conditions were right to accelerate growth with more money.

As far as the public markets, “You want to go public at a time when you have visibility to a few years of growth, and you want to be cash-positive, or very close,” both of which he has in his sights.

Many schemes have emerged in decades past to bridge or close the digital divide, including the digital subscriber line battles of the competitive local exchange carriers twenty years ago. The BEAD money will be “the big program for the next year and a half,” says Alwan. “That’s when we’ll know how much actually finds its way to fixed wireless or fiber or this or that.”

The biggest challenge for Tarana in the meantime is getting out the word to the prospective operators that wireless is becoming the long-sought wireline alternative.

“It hasn’t hit a general consensus yet, the world hasn’t accepted this yet,” says Alwan. “But, it’s on the verge now because the proof points are there.

Disclosure: Tiernan Ray owns no stock in anything that he writes about, and there is no business relationship between Tiernan Ray LLC, the publisher of The Technology Letter, and any of the companies covered. See here for further details.